What is Poisson’s Ratio?

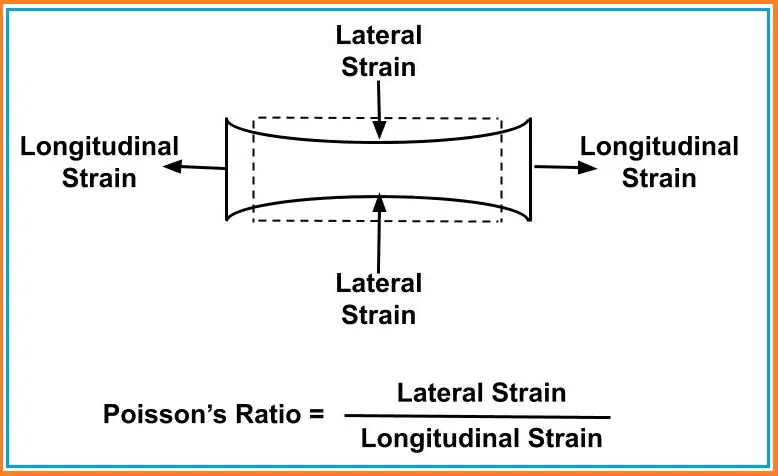

Poisson’s ratio of a material is a very important parameter in material science and engineering mechanics. When a force is applied to a bar it deforms (elongates or compresses) in the axial (longitudinal) direction. At the same time, a deformation is observed in the transverse (width) direction as well. Poisson’s ratio relates these changes in the transverse direction and axial direction. This effect is known as Poisson’s effect which is named after the French mathematician and physicist Simeon Poisson. The Poisson’s ratio is defined as the ratio of the transverse strain to that of the axial strain under the influence of the same force. It is a material property and remains constant.

Poisson’s Ratio Formula

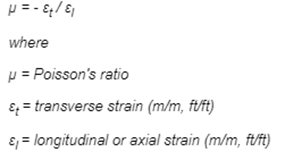

Let’s deduce the formula for Poisson’s ratio. From the above definition, Poisson’s ratio can be expressed mathematically as

Poisson’s Ratio=Transverse (Lateral) Strain/Axial (Longitudinal) Strain

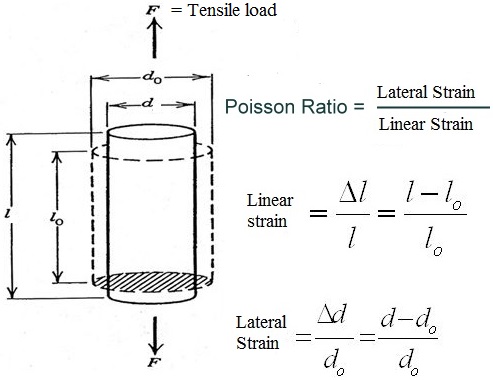

Let’s understand this philosophy using the example in Fig. 2. In this image, A tensile force (F) is applied in a bar of diameter do and length lo. With the action of this force F, the bar elongates and the final length is l. Also, the diameter reduces and the final diameter is d.

So from the above, Axial Strain, Longitudinal Strain, or Linear Strain= (Change in Length/Original Length)=(l-lo)/lo. Similarly, Lateral Strain or Transverse Strain=(Change in Diameter/Original base Diameter)=(d-do)/do. So, as per the definition, the equation of Poisson’s Ratio or Poisson’s ratio formula can be written as follows

Poisson’s Ratio=Lateral Strain/Longitudinal Strain={(d-do)/do}/((l-lo)/lo}= lo(d-do)/do(l-lo)

Poisson’s Ratio Example

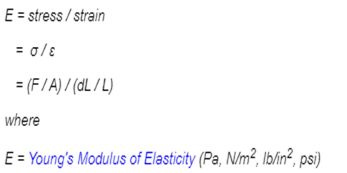

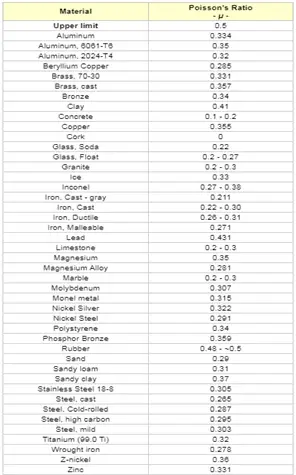

Similar to Young’s modulus, Poisson’s Ratio is the property of a material and is constant. However, the value of Poisson’s ratio changes with temperature. Young’s modulus, the shear modulus, and the bulk modulus are related to Poisson’s ratio. For these modules to have positive values, the Poisson’s ratio of a stable, isotropic, linear elastic material must be between −1.0 and +0.5. The value of Poisson’s ratio normally ranges between 0.0 and 0.5. The following table provides a few typical values (range) of Poisson’s ratio for common materials.

| Material | Poisson’s Ratio |

| Carbon Steel | 0.27–0.30 |

| Cast iron | 0.21–0.26 |

| Stainless steel | 0.30–0.31 |

| Aluminium-alloy | 0.32 |

| Copper | 0.33 |

| Inconel | 0.27-0.38 |

| Gold | 0.42–0.44 |

| Silver | 0.37 |

| Platinum | 0.39 |

| Glass | 0.18–0.3 |

| Foam | 0.10–0.50 |

| Sand | 0.20–0.455 |

| Molybdenum | 0.307 |

| Concrete | 0.1–0.2 |

| Clay | 0.30–0.45 |

| Tin | 0.33 |

| Titanium | 0.265–0.34 |

| Magnesium alloy | 0.252–0.289 |

| Rubber | 0.48-0.4999 |

| Brass | 0.331 |

| Bronze | 0.34 |

| Ice | 0.33 |

| Lead | 0.431 |

| Monel | 0.315 |

| Nickel | 0.31 |

| Polystyrene | 0.34 |

| Limestone | 0.2-0.3 |

| Nickel Steel | 0.291 |

| Tungsten | 0.28 |

| Metallic Glass | 0.276–0.409 |

| Boron | 0.08 |

| Beryllium | 0.03 |

| Cork | 0.0 |

| Re-entrant foam | -0.7 |

Unit of Poisson’s Ratio

Poisson’s ratio is the ratio of two strains. Both longitudinal and lateral strains are dimensionless. So Poisson’s Ratio is dimensionless. There is no unit for Poisson’s Ratio.

Symbol of Poisson’s Ratio

Poisson’s ratio is normally denoted by the Greek letter ν (nu). However, this is not standardized. So users can use any symbol for Poisson’s ratio at their discretion.

What is Negative Poisson’s Ratio?

In general, for common materials, the cross-section becomes narrower when stretched. So, Poisson’s ratio is positive for most materials. However, certain materials (Origami-folded materials, certain solid woods, and certain crystals) show a negative Poisson ratio. This means when they are stretched in the longitudinal axis, their cross-sectional area increases. The main reason behind such type of behavior is due to their uniquely oriented, hinged molecular bonds. These materials are known as auxetic materials. Note that, more than three hundred crystalline materials have negative Poisson’s ratio in certain states. Some of the typical examples of auxetic materials are Li, Cu, Rb, Na, K, Ag, Fe, Ni, Co, BAsO4, Cs, Au, Be, Ca, Zn Sr, Sb, MoS2, Living bone tissue, Non-carbon nanotubes, Auxetic polyurethane foam, Chain organic molecules, etc.

Applications of Poisson’s Ratio

Poisson’s ratio is a very important parameter of materials. In engineering mechanics, the strength of materials, structural engineering, machine design, and fluid flow problems, Poisson’s ratio finds wide application. Some of the common applications of Poisson’s ratio are listed below:

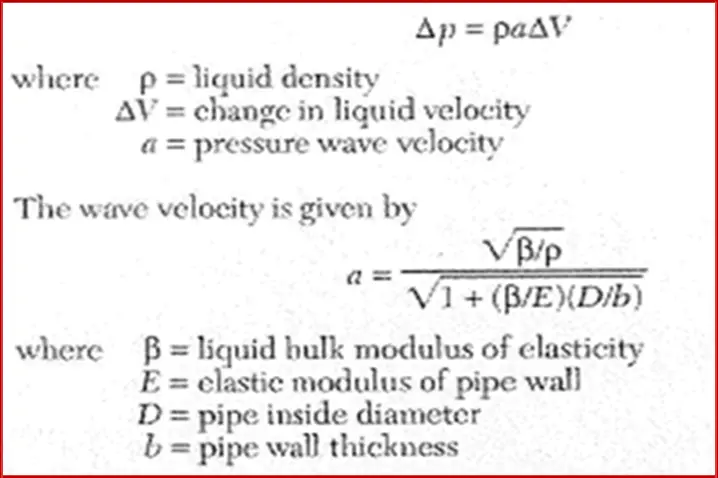

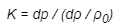

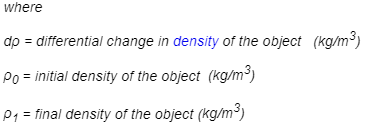

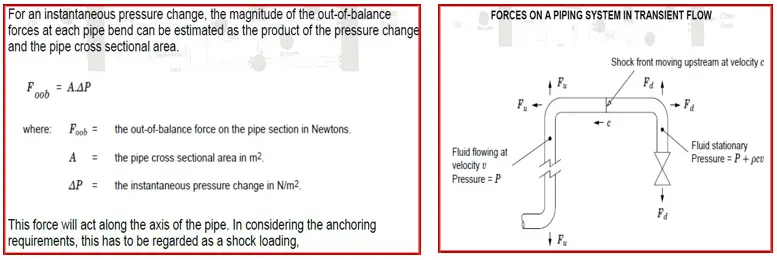

In pressurized pipeline flow problems, Poisson’s effect has a significant influence. The internal pressure creates hoop stress in the pipe material. Due to Poisson’s effect, this hoop stress causes the pipe to increase in diameter and slightly decrease in length.

For studying the effect of stress, strain, and modulus of materials, the Poisson’s ratio plays an important role. It is an important parameter while converting from one modulus to the other.

The near-zero Poisson’s ratio for Cork material makes it ideal as bottle stoppers.

In structural engineering, Poisson’s ratio is essential for analyzing the deformation and stability of structures. It helps engineers predict how materials will respond to different load conditions.

Engineers use Poisson’s ratio in the design and manufacturing of components to predict and control deformations. This is crucial in ensuring that structures and products meet safety and performance requirements.

Poisson’s ratio is crucial in the design and analysis of composite materials, where different materials are combined to achieve specific mechanical properties. Understanding how these materials deform is essential for their effective use.

FAQs related to Poisson’s Ratio

In this section, we will try to answer some of the frequently asked questions related to Poisson’s Ratio to clarify the subject better.

What is Poisson’s Ratio?

Poisson’s ratio of a material is defined as the ratio of the lateral strain (change in the width per unit width of a material) to the axial strain (change in its length per unit length) due to the action of a Force.

What does a Poisson ratio of 0.5 Means?

Poisson’s ratio of 0.5 signifies that due to the application of a force the deformation change in the width direction is half the deformation change in the axial direction. Normally, for perfectly incompressible isotropic materials the value of Poisson’s ratio is 0.5. Rubber is a typical example.

What is the Poisson’s Ratio of Steel?

The Poisson’s ratio of steel is normally 0.27 to 0.30. When more authoritative data from tests are not available, normally 0.3 is used in design calculations as Poisson’s ratio of Steel material.

Can Poisson’s ratio be greater than 1?

For isotropic material, Poisson’s ratio can not exceed 0.5. However, for anisotropic materials, the value of Poisson’s ratio can be greater than 1 in certain directions. For example, polyurethane foam.

Why Poisson’s ratio is important?

Poisson’s ratio of a material is very important for studying the stress and deflection properties of engineering materials like pipes, beams, vessels, etc.

What if Poisson’s Ratio is Zero?

The Poisson’s ratio of Zero means it does not deform in the lateral direction during elongation or compression in the axial direction by the application of a force. The material Cork is believed to have a near-zero (~0) Poisson’s ratio. This is the reason Corks are ideally used as bottle stopper as it does not expand even when compressed.

Which material has the highest Poisson ratio?

Ignoring specifically designed anisotropic materials, Rubber has the highest value of Poisson’s ratio at 0.4999.

What is the Poisson’s Ratio of Aluminum?

The Poisson’s ratio of Aluminum normally varies between 0.3 to 0.35.

What is the Poisson’s Ratio of Concrete?

The Poisson’s ratio of Concrete normally varies between 0.1 to 0.25. For design calculation, in the absence of data, normally 0.2 is used as Poisson’s ratio of Concrete.

Few more related articles for you.

Introduction to Stress-Strain Curve (With PDF)

Stress or Strain: Which comes first?

Hooke’s Law: Statement, Equation, Graph, Applications, Limitations (With PDF)

Young’s modulus: Young’s modulus of Steels [With PDF]